Design Ensemble: Two Sides of the Same Coin

February 6, 2022

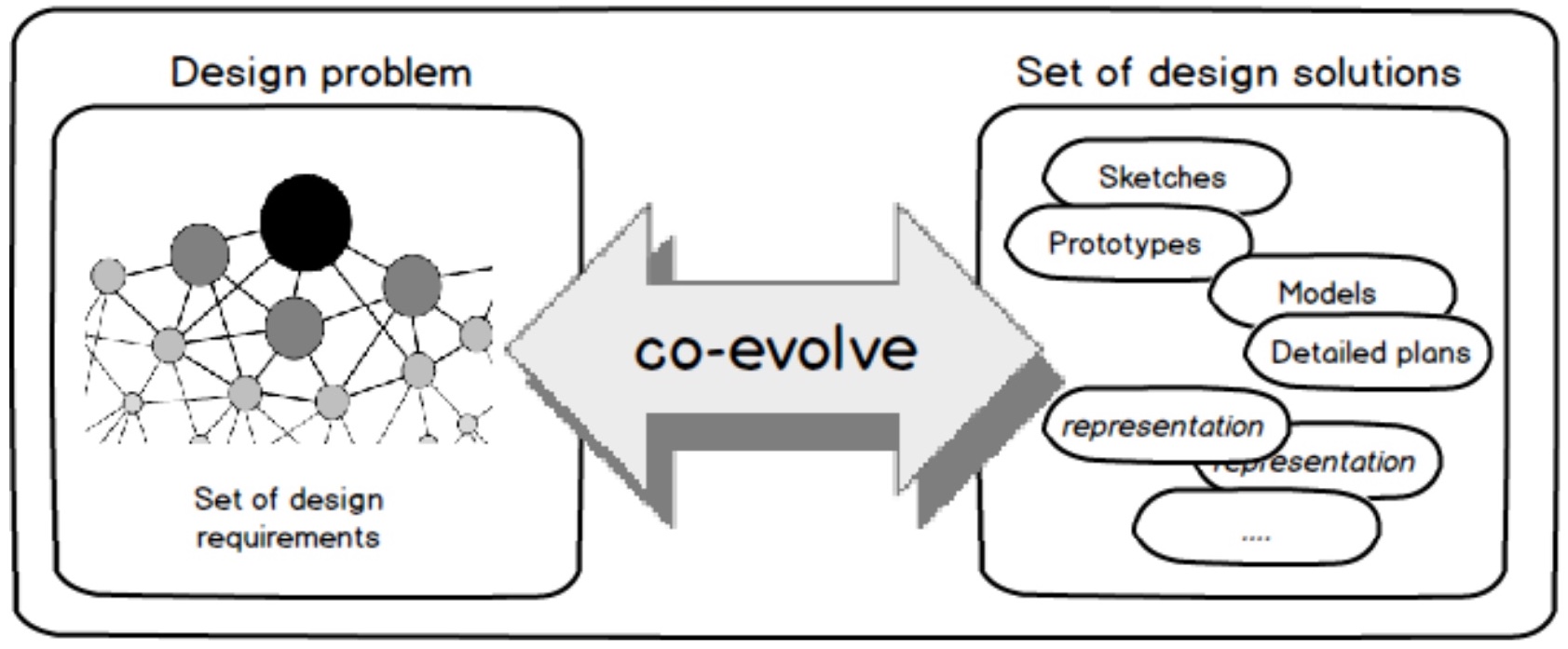

One can view a design problem, P, and its associated set of solutions, S, as a single unit called a design ensemble, or as “two sides of the same coin.”

The figure below illustrates this perspective of design. In the left-to-right direction, a description of a design problem can be encoded as a set of design requirements (DRs), which then directly influence the development of design solutions. And in the opposite direction, developed design solutions influence further elicitation and refinement of DRs.

This formal “design ensemble” perspective of design is compatible with the broadly accepted notion that designing consists of both the problem analysis (i.e., the exploration of what to design), and the solution synthesis (i.e., figuring out the parts of the solution and structuring them together).

If we assume that a state of a design project is described by the pair (P, S), we are in a position to postulate yet another definition of designing:

To design means to co-evolve the design problem and its associated set of design solutions, in other words, to co-evolve the design ensemble (P, S).

This is in addition to some other extant definitions of design (see, for example, this post in which I cite three additional and useful definitions of design).

Literature corroborates the “co-evolving design ensemble” view of designing. For example, Cross (2001) states that “designers move rapidly to early solution conjectures, and use these conjectures as a way of exploring and defining problem-and-solution together”. Dorst and Cross (2001) further confirm the hypothesis that design problems and their solutions co-evolve in parallel, by conducting protocol studies involving experienced designers.

Further, in mechanical engineering design, Ullman, Dietterich, and Stauffer (1988) describe the evidence that designers introduce new, additional design requirements (DRs) as they proceed with design: (1) those based on the designer’s pre-existing domain knowledge and (2) those derived by evaluating potential design solutions. This indicates the “back” flow of knowledge (from S to P), in addition to the default forward flow from P to S.

In a similar vein, Maher and Poon (1996) propose a model for “creative design” based on exploring the problem-solution tandem in parallel, using genetic algorithms to evaluate the fitness of individual design solutions. In yet another article describing a protocol study involving architectural designers performing tasks in parametric design environments, Yu, Gu, Ostwald, and Gero (2014) confirm the co-evolution hypothesis as well.

In conclusion, the “co-evolving design ensemble” view represents yet another useful tool in our arsenal of available abstractions, models, and conceptualizations of design. It would perhaps be interesting to explore how this formalism meshes with other established constructs in design research, such as, for example, the notion of “design space”, situated design, and cyclic models of cognition.

References

-

Herbert Alexander Simon. The sciences of the artificial. MIT press, 1996.

-

Nigel Cross. Design cognition: Results from protocol and other empirical studies of design activity. Design knowing and learning: Cognition in design education, 7:9–103, 2001.

-

Kees Dorst and Nigel Cross. Creativity in the design process: co-evolution of problem–solution. Design studies, 22(5):425–437, 2001.

-

Donald A Schön. The reflective practitioner: How professionals think in action, volume 5126. Basic books, 1983.

-

David G Ullman, Thomas G Dietterich, and Larry A Stauffer. A model of the mechanical design process based on empirical data. AI EDAM, 2(1):33–52, 1988.

-

Mary Lou Maher and Josiah Poon. Modeling design exploration as co-evolution. Computer-Aided Civil and Infrastructure Engineering, 11(3):195–209, 1996.

-

Rongrong Yu, Ning Gu, Michael Ostwald, and John S Gero. Empirical support for problem–solution coevolution in a parametric design environment. Artificial Intelligence for Engineering Design, Analysis and Manufacturing, pages 1–12, 2014.